Why We’re Bad at Math and Have Diabetes

Illustration by Mauricio Antón. © 2008 Public Library of Science

We’ve been hunter-gatherers for 99% of our history. We used to walk between five and ten miles a day, consume five pounds of sugar each year, and scour all day for sources of fat. We craved calorie-rich foods and our bodies figured out how to store energy to survive frequent bouts of famine.

We now live in a materially different environment. The average American now walks about one-third as far, consumes 25 times more sugar, and has ample access to caloric and fatty foods.

Our bodies are wired for famine, but we now live in abundance. As a result, we overeat and struggle to metabolize the excess sugar and fat, leading to obesity and type 2 diabetes. These chronic conditions are mismatch problems partially caused by a gap between our environment and our biology. A mismatch problem occurs when the traits that helped us thrive in our evolutionary past become inadequate in our new environment.

Mismatch problems also exist in the brain. Just as our endocrine system didn’t evolve to handle a high sugar intake, our minds didn’t specifically evolve to create art, philosophize, or make complex decisions.

Consider the Linda problem made famous by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in 1983 [PDF]:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

A. Linda is a bank teller.

B. Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

If you’re like 85% of people, you’ll choose B because the description of Linda makes her sound like a feminist bank teller. However, basic probability reminds us that there must be more bank tellers than feminist bank tellers, as the latter is a subset of the former, so A must be more probable. This error is known as the conjunction fallacy.

Just as we can’t blame our bodies for struggling to keep our blood sugar stable after eating processed foods, we can’t fault our minds for making mistakes when asked to interpret abstract conjunctions. It’s unlikely that ancient humans needed to ruminate on conjunction problems to excel in the age of the woolly mammoth, so it’s no surprise we make these mistakes. In this way, being bad at abstract probabilities is like having diabetes — these simply aren’t problems that our evolutionary ancestors needed to handle.

How can we solve mismatch problems? We often attempt to enhance our capabilities through education. Unfortunately, the food pyramid is no match for biology programmed to devour the bulk bag of candy that awaits us in the kitchen.

Instead of trying to band-aid our biology, we should focus on shaping our local environment. We can craft our surroundings, which we often control, to promote the desired behavior. If we don’t buy bulk bags of candy, we won’t need to exhaust willpower to fight the inevitable temptation to overindulge.

The same technique applies to the Linda problem. By reshaping the problem with natural fractions that represent our experience of the world, fewer than 15% of people violate the conjunction rule (Hertwig & Gigerenzer, 1999 [PDF]):

In an opinion poll, the 200 women selected to participate have the following features in common: They are, on average, 30 years old, single, and very bright. They majored in philosophy. As students, they were deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Please estimate the frequency of the following events.

How many of the 200 women are bank tellers? ____ of 200

How many of the 200 women are bank tellers and are active in the feminist movement? ____ of 200

Humans have been evolving for about two million years, but the demands of today are a substantial shift from our past. Our diet has changed dramatically in the last few thousand years, and we started using probabilities only a few hundred years ago. Our genetics simply haven’t had time to catch up.

In the meantime, we are simply caught in a state of disequilibrium between our genes and our environment. We shouldn’t hold ourselves to unreasonable normative standards in light of our evolutionary past. While we can’t yet easily change our genes, we can architect our environment to promote the behavior we desire.

Everything You Thought About Behavioral Economics Is Wrong

The well-known story of how the Economist magazine’s clever pricing led to a dramatic increase in premium subscriptions – an example of the asymmetric dominance or decoy effect1 – is probably incorrect. And it doesn’t really matter.

Two separate journal articles published this year have failed to replicate this classic finding after multiple attempts with thousands of participants (Frederick, Lee, & Baskin, 2014; Yang & Lynn, 2014). These studies have helped clarify that the asymmetric dominance effect generally only occurs with salient, numerically-defined attributes in which the dominance relationship is readily encoded. In the Economist example, the choices are defined by a jumble of words and numbers. It is much easier to compare $59 to $125 than “Economist.com subscription” to “Print & web subscription.” Combining these two dimensions mutes the effect.

Why did the example “work” ten years ago and why is it “not working” today? Nobody knows. Perhaps the concept of a print magazine is simply less relevant in 2014. Perhaps participants in earlier studies were unintentionally biased in some unrecognized manner. Perhaps the random perturbations of behavior flew under the arbitrary 5% level in statistical significance testing [pdf].

The true reason for the discrepancy, if it could be determined, is irrelevant. The Economist example teaches us this crucial lesson: behavioral science research cannot tell us what will or will not translate into the real world. Nor does it claim to. All it can do is suggest ways of thinking about the problem and point us in some general directions for experimentation.

Taken together, the behavioral science literature represents a tour de force of how bad we are at things we think we are pretty good at. There is not – and can never be – a grand theory that explains all of these observations. Behavioral decision theory is not a closed-ended discipline. We have some decent constructs and psychological models, but behavioral predictions in multifactorial decision contexts are hard to make and even harder to defend. I admire and applaud authors who deftly translate academic research into accessible vignettes for a general audience, but stories lifted from academic journals are not designed to translate directly into the messy real world. That’s precisely why the Economist example might not work today, and that’s why it doesn’t matter whether it works.

This reality ought not discourage. While human behavior is complicated, the heuristic value of this research is substantial, and applications to public policy and health care are particularly encouraging. It will simply require leaders with intellectual honesty, perseverance, and a dedication to experimentation to derive practical value from the groundwork laid by decades of research.

1 If you need a brief primer on asymmetric dominance, Wikipedia has a decent article. To be fair, this is not a pure example of the asymmetric dominance effect, as the third option completely dominates the second, but this is a distinction unimportant to the broader point.

A First Look at Competition and Price on the Federal Health Exchange Marketplace

The federal health insurance exchanges launched in 2013 to a modestly encouraging but tepid insurer response. Anxious at the prospect of developing consumer insurance products to be sold through a relatively untested channel and targeted at a challenging demographic, many large insurers adopted a wait and see approach. While the marketplaces exceeded enrollment targets and enabled millions of Americans to purchase insurance, consumers in many markets faced limited options. In several states, such as New Hampshire, Mississippi, and Rhode Island, only one or two insurers participated on the exchanges.

Core to the public insurance marketplace thesis was the concept that a larger individual insurance market would attract competition, which would in turn reduce prices. However, many in the industry understood that competition on the exchange would not mature overnight. Prior to the Affordable Care Act, it was not uncommon for the dominant player in a state’s individual insurance market to enjoy a 50% market share. As coverage year 2015 health exchange filings become available, we can start to examine the relationship between market competition and insurance premiums on the federal exchange.

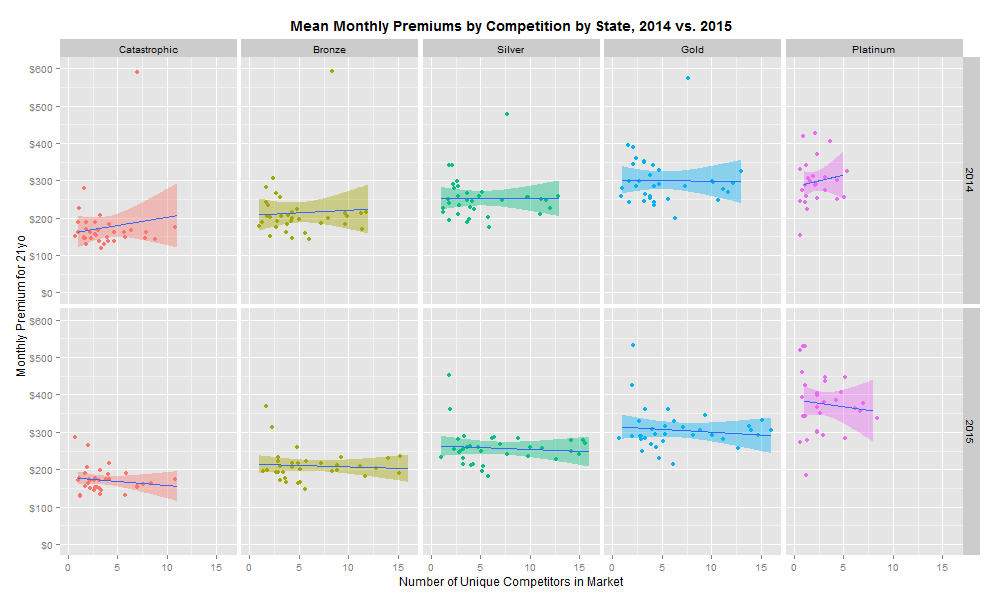

My first analytical approach was to plot the mean monthly premium in each state (by coverage level) against the number of unique insurers in each market (see R code on Github). A basic linear regression of premiums by number of unique insurers and by coverage level revealed no significant relationship.

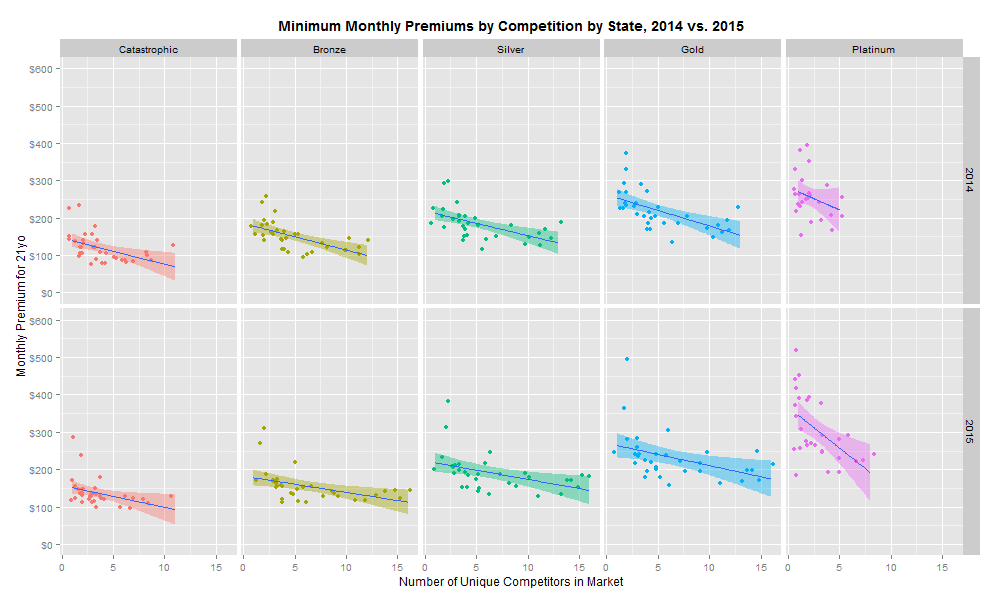

This is clearly a disappointing discovery. However, it is possible that the important unit of analysis is not the mean premium in each market, but instead the minimum premium in each market. Repeating the same analysis with the lowest premium as our dependent variable reveals the following:

There is a significant negative relationship between increased competition and health insurance premiums for all coverage levels in 2014 and 2015. The regression model (collapsing 2014 and 2015 rates) suggests that each incremental market entrant corresponds to a 3.4% reduction in monthly premiums. Moreover, this trend continued as more entrants entered the market in 2015. However, linear regressions by year suggest that the size of the competition relationship is decreasing: the effect of an incremental insurer on premiums was -3.7% in 2014 and -3.1% in 2015.

A variety of potential factors could explain this pattern:

- As more insurers enter a market, the relatively fixed population is fragmented across a larger number of discrete risk pools, which leads to greater actuarial risk. However, an insurer with a dominant market share or national footprint may pool primary or secondary risk. A reduced risk profile should lead to lower premiums.

- In some markets, the past decade of provider consolidation afforded integrated delivery systems and academic medical centers with more negotiating leverage, which has led to higher contract rates. This may pose a particular challenge to new or young insurers (10-15% of the exchange market) that lack the patient volume to obtain the deep discounts required to compete on price.

- Selling insurance directly to consumers contributes to substantially higher marketing and administrative costs. However, national carriers may benefit from some scale efficiencies. Larger markets likely attract more insurers, and national insurers with potentially lower administrative costs are more likely to participate in these markets.

- Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) requirements squeeze all insurers into a narrow margin band, which deters all but the most confident and price competitive entrants. A failure to reduce mean premiums might imply that insurers are approaching a theoretical local maximum on profitability. Low margins, even on high top-line revenue, might impinge insurers’ abilities to invest in innovative benefit designs and reimbursement structures to dramatically improve savings.

These are some plausible factors that may contribute to the observed patterns, and it is important to not read too closely into such a simple analysis. The key challenge behind this dynamic is that the nature of price competition is still predominantly volume-based and not value-based. In other words, insurers in this market reduce costs by leveraging the number of patient lives they have to obtain discounts from providers, and not by fundamentally changing the incentive structures to reward cost effective improvements in patient outcomes. Only through the proper alignment of reimbursement with outcomes will our system be able to drive the transformative reduction in total costs and improvements in patient care.

What a 225 Year Old Mozart Opera Can Teach Us About the Brain

Warning – this is a bit dense!

Le Nozze di Figaro, commonly known as The Marriage of Figaro, is a comedic opera written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1786. The opera portrays the dramatic trials and tribulations of the soon-to-wed Figaro and Susanne as they progress through a series of feudal customs. While the story itself might be less familiar to the reader, the opera’s overture – Cavatina No. 3 (often referred to by its text incipit as Se vuol ballare) – is one of Mozart’s best-known pieces. The music world has studied Le Nozze for centuries, but the emerging field of music cognition presents new opportunities for novel analyses. So, what can a 225 year old opera teach us about the brain?

Musical Accentuation as Cognition

In the cavatina, Figaro flaunts his plans to thwart the Count, who plans to exercise his “feudal rights” with Figaro’s fiancée. Given the importance of this cavatina in the overall opera, Mozart set the text in a specific accentual pattern to highlight specific words that indicate Figaro’s emotional state. Interestingly, these factors create extra accent by diverging from the set metrical patterns and places extra emphasis on the word “si” to supplement the emotional plot developments. The poetic structure and musical accentuation in Se vuol ballare drives the complex rhythmic pattern that structures the listener’s perception of the piece within the overall plot of the cavatina. Using the Italian textual accentuation rules set forth by Balthazar (1992), I analyzed the poetic structure and accentuation in the No. 3 Cavatina (Figure 1). The divisions of the bars and text/notation subdivisions are derived from an equal combination of the auditory perception of the piece and the musical score.

Figure 1: Poetic structure and accentuation in No. 3 Cavatina from Mozart Le Nozze

P = piano text setting

T = trunco text setting

S = sdrucciolo text setting

A = agogic accent

ME/T = metrical/textual accent

HM = hypermeasure

1 = words correspond roughly 1:1 with the first violin voice, textual accents match with agogic

2 = words do not correspond roughly 1:1 with violin voice

3 = strong disparity between metrical and agogic accents – feels like two separate beats

Hypermeasure = corresponds with hyperbeat for the motive for each section

Major accent = corresponds to location of most salient accent within each hyperbeat (note location/hypermeasure)

* = only a partial hypermeasure

Blank spaces indicate indeterminable or insignificant patterns

It is clear from Figure 1 that a pattern of A, B, C, D, A’, and E emerges, where the capital letters designate overall sections. Within these major sections are smaller text and notation subdivisions that are separated based on the coherence between Figaro’s vocal notation with the major first violin score. For example, section A involves an overarching rhythmic notation and textual pattern between measures 1-42. It includes the subdivided section of A1 in which Figaro’s notation follows roughly in a 1:1 pattern with the first violin notation in terms of pitch variation and note length, a section of A2 in which the words do not correspond with the first violin notation, and a second A1 section similar to the first A1 subdivision. This chart matches the auditory experience of the piece in which the beginning sections start with similar measures 1-42 consistent in content and musical notation.

Next, measures 42-55 contribute to the beginning of a climax in which the text is mismatched with the musical notation of the violin parts. Subsequently, measures 56-63 provide a connection between the more dramatic sections with the impending subdivision in measures 64-103 that contribute to the most significant climax in the cavatina. In this section, Figaro flaunts his plans to beat the Count at his own game, which is the central theme of the aria.

Finally, Figaro repeats the opening lines in measures 104-122, and measures 123-131 provide a flourish of instrumentation to mark the end of the cavatina. The interplay between the 3/4- metered of sections A, B, C, A’, and E interrupted by the 2/4 metered subdivision of D emphasizes the climactic structure of the piece. The patterns in notation and plot provide Mozart with fertile ground for the manipulation of the listener’s attention through deliberate accentuation.

Mozart’s use of segmentation created by piano endings in the subdivided 3/4-metered sections of the first A1, second A2, C2, and A1’ create a pattern of accentuation to which the listener’s attention becomes entrained. The combination of the musical elements in this section results in a specific pattern: trunco (where the final syllable is accented) and piano (where the penultimate syllable is accented) text setting endings are combined with significant auditory accents caused by metrical/textual accents in coincidence with agogic accents (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Pattern of Metrical/Textual & Agogic Accents in Measures 1-8 of Le Nozze

Moreover, the compounding of these accents is exacerbated through its interaction with the textual accents. Figure 3 displays the segmentation of the lyrical content in the first A1, second A2, C2, and A1’ sections. A pattern of quinario lines with piano and/or trunco endings combined with a metrical/textual notational accent on the stanza-end quaternario line with either sdrucciolo (where the antepenultimate syllable is accented) or trunco endings develops a strong pattern of accentuation in these sections. Additionally, the melismaticism created by the presence of alternating or consistent quarter notes per line for each quinario ending increases the power of the metrical entrainment. This pattern repeats throughout the piece, lending credence to the notion that Mozart deliberately used the combination of piano and trunco endings with textual and agogic accents to provide an entrainable rhythm that drives the listener’s perception of the cavatina.

Figure 3: Segmentation in No. 3 Cavatina from Mozart Le Nozze

STA = stanza number

REP = indicates repetition

QPL = quarter notes per line

MT/E = metrical/textual accent

Scansion = ending

The grouping of the abovementioned notational and accentual effects generates a hypermeasure that is then shifted by abnormal accentuation on the word “si.” The metric grid in Figure 4 for measures 1-4 of No. 3 of Le Nozze di Figaro demonstrates the various Metrical Performance Rules (MPRs) outlined by Lerdahl & Jackendoff (1983). Figure 4, when considered along with Figure 1, reveals a two-bar hypermeasure with a the major accent (combination of metrical/text accent and agogic accent) in section A1 of the cavatina. This two-bar hypermeasure is similar in construct in terms of the MPR rules in measures 9-12, although the major accent that anchors the hypermeasure shifts to the 7th beat in the sequence. Measures 13-16 should have been structurally similar to measures 1-4. However, the existence of the extra word “si” shifts the hyperbeat to a position more distant from the major accentual position, which is on the 4th running beat (first note of the second measure) of the 13-16 measure segment. While the metric grid differences between measures 1-4 and 9-12 are significant, they are consistent with a simple shift in major accentuation position, whereas the shift between measures 1-4 and 13-19 constitute an entire displacement of the hypermeasure. It is important to recognize that an extra quarter note in the first violin voice at the 11th position in measures 13-16 creates a whole note at that position. This additional note helps shift the beat that anchors the hypermeasure. This finding is significant because it reveals that this hyperbeat shift is caused directly by the unique accentuation of the word “si.” This departure from the expected attentional oscillations implies that the word “si” garners the listener’s attention by disrupting the expected rhythmic patterns.

Figure 4: Metric Grid for No. 3 Cavatina from Mozart Le Nozze (mm. 1-4, 12-19)

The Link between Lyrical and Musical Attention

This analysis reveals that the combination of primary metrical/textual and agogic accents interacts with the piano and trunco line endings to give rise to a hypermeasure that is shifted with the addition of the word “si,” thus breaking the listener’s internal attentional oscillations. Considered within the context of the cavatina, in which an interplay between the 3/4 measure segments and 2/4 measure segments gives rise to a climax consistent with the plot of the opera, the early and repeated shift in attention plays an important role in the listener’s perception of the storyline. By punctuating Figaro’s opening sentiments about his interaction with the Count through the addition of the word “si,” Mozart disrupted listener attention to highlight the emotional climax of the plot. The interruption of the attentional oscillation introduced by the word “si” suggests that Mozart had an intuitive understanding of the interplay between lyrical and musical attention — a finding that music researchers discovered over 100 years later.

References

1. Balthazar, Scott L., “The rhythm of text and music in ottocento melody: An empirical reassessment in light of contemporary treatises,” Current Musicology 49 (1992): 5-28; adapted from Robert A. Moreen, “Integration of text forms and musical forms in Verdi’s early operas” (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1975).

2. Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. “Theoretical Perspective.” In A Generative Theory of Tonal Music, 1-31. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1983.

Modern Insurance Requires Behavioral Economics

Traditional insurance prices health products and services according to their cost. Formularies, which are the schedules of drug benefits created by insurance plans, operate under a one size fits all model. As a result, insurance plans inadvertently discourage many health behaviors with high clinical value by charging for them at prices irrespective of their benefit to the patient. This leads to misaligned incentives and suboptimal outcomes. For example, a 2004 study demonstrated that decreasing medication co-payments for patients with coronary heart disease (the leading cause of death [pdf]) from $20 to $10 increased medication adherence from 49% to 76%. Poor medication adherence alone accounts for about 15% of total health care [pdf] spending in the United States, and a nontrivial portion of this expense could be prevented by removing cost barriers to accessing medications.

Value-Based Insurance Design

Value-based insurance design (VBID) aims to solve the failure of the cost-based, one size fits all approach. VBID acknowledges decades of behavioral economics research demonstrating that humans do not follow the strict axioms of rational decision making. VBID recognizes patient heterogeneity and adjusts out-of-pocket costs to match the expected clinical benefit according to evidence-based research. While traditional insurance design pairs a patient with an insurance product, the value-based insurance product is optimized for the patient, who is unable to properly assess the costs and benefits of most clinical options. VBID suggests that a patient with coronary heart disease should have lower co-payments for medications that drive the best outcomes. An insurance plan might also waive co-payments for routine physician visits for patients with chronic disease. These outpatient interactions are designed to monitor health, ensure medication adherence, and spot early indications of condition deterioration – often preventing expensive emergency inpatient care. VBID typically offers disease prevention programs promoting physical activity and proper nutrition at little to no cost. Type 2 diabetes adds an average of $85,000 in lifetime health care costs, so the expected outcome of preventive measures is often worth the up-front investment, as at least one empirical study has shown. At the same time, VBID discourages the use of high cost, low value services. Identifying these services is challenging and sometimes controversial, but there are obvious interventions that reduce systemic costs. Colonoscopies in the same city frequently vary in price by up to 300%. VBID often implements reference pricing to reduce overpaid diagnostic tests. Value-based insurance design helps alleviate the patient decision burden by incentivizing the high value services that improve health outcomes.

The Challenge of Economic Incentives

The Affordable Care Act follows the value-based insurance approach by permitting incentives for favorable behaviors, such as smoking cessation, weight loss, and exercise. These incentives are primarily economic – e.g., insurers may levy a 50% premium surcharge for smokers. Will it work? The empirics tell a mixed message. While 87% of large employers offer wellness programs, participation rates are abysmally low (5% to 8%). Benefit consultant Towers Watson predicted that an incentive of $350 per employee would be required to boost health risk appraisal (HRA) participation above 50%. The story is worse for more involved wellness programs that could meaningfully impact health outcomes and costs. Fewer than 10% of employees even attempt to enroll in a weight loss program, even when offered $600 or more to participate. Economic incentives are a necessary but insufficient component of value-based insurance design.

Behavioral Sciences and Population Health

The rules of trade will be rewritten as our health care system reorients towards population health. In the coming decade of care delivery and reimbursement experimentation, the roles of payers (“payors”), providers, and employers will shift in potentially dramatic ways. Accountable care organizations (ACOs) paid under some combination of capitation and fee-for-service with shared savings arrangements will shift risk to providers, who will be incented on patient outcomes. With the shift from reactive treatment and hospitalization to proactive prevention, many revenue line items on a hospital P&L will swap places with expenses. A real challenge for payers and providers in the coming decade will be to orchestrate behavioral change at scale – using techniques that go beyond economic incentives. But who owns these capabilities? Providers know how to treat illness. Insurers understand how to manage actuarial risk. And self-insured employers know how to write big checks. How can physicians conduct patient outreach and activation? What tools can they use to encourage patients to join weight loss programs, change their diet, or start exercising? And how do they monitor and coach patients through these behavioral changes?

The behavioral sciences will play an important role in this transformation, but the current capability gap is enormous. We know more about an individual as a consumer of discretionary products than as a consumer of essential health services. And we do more to convince the former to buy expensive headphones than the latter to get a flu shot. The academic community has proactively increased research at the intersection of health and decision theory. Most notably, the University of Pennsylvania’s schools of medicine, law, and business have joined together with Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Behavioral Decision Research to form the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics (CHIBE). But we can start with the existing playbook used by advertisers and begin applying these techniques more aggressively to drive health outcomes and improve lives. We can’t afford to do otherwise.