Preferences are Strange

There’s a lot of confusion about preferences and why we care about them. Here are five important reminders when thinking about preferences:

You can’t measure actual preferences

There’s no direct measure for preferences, so we have to use a variety of methods to elicit preferences. Perhaps the strongest way to elicit preferences is to ask people to make choices between alternatives. We can also ask people to reveal their willingness to pay (WTP) using an incentive-aligned technique like the Becker–DeGroot–Marschak method. Or, we can ask people to tell us how much they like an option. These are all proxies for the real, underlying preferences that people have but can’t expose directly. Importantly, different methods of measuring preferences should not yield different preferences.

Preferences can’t be correct or incorrect

Normative prescriptions for preferences don’t exist. Each of us will have different preference functions in a given context; we can’t deem a preference correct or incorrect.

There are multiple ways to determine if preferences are good

Ultimately, we care about consistent preferences because we believe that good choices maximize expected utility. A rational decision maker will attempt to pick the best option. If people routinely make choices that don’t maximize utility, then they’re making suboptimal choices. The consistency between what you expect to maximize utility and what actually maximizes utility is one measure to determine good preferences.

Making good choices is hard

It’s quite difficult to maximize utility. For example, you can’t really ask someone “is eating that banana the best thing you could be doing with your time and money?” What would they say? Most people don’t think about opportunity costs in an explicit manner; notable exceptions are low income individuals and lawyers (e.g., “This party is costing me $3,000!”). In addition, a lot of noise can get in the way of making good decisions. When we’re rushed or distracted, it’s no surprise we make suboptimal choices.

Even though we make lots of mistakes, only some are interesting

Modern behavioral economics has adopted a view of bounded rationality, which holds that we can’t globally optimize our choices to maximize utility. Instead, we’re bounded by the limits to our cognition and the decision environment, like time pressures. With this view, the interesting mistakes are the ones that are systematic (i.e., mistakes that cut across choices, contexts, and preferences). When we look at these systematic mistakes, we uncover the heuristics (shortcuts) that lead to biases in choice. The attempt to explain these patterns constitutes the foundation of behavioral economics.

A Psychologist, Behavioral Economist, and Marketing Scientist Walk into a Bar…

Under the umbrella of behavior science sit multiple disciplines that contribute to our understanding of decision making. In popular parlance, many of these insights get lumped together as “behavioral economics,” but this is a muddled view of the complex interaction between many related but distinct disciplines. (In fact, despite winning a Nobel Prize in Economics, Daniel Kahneman claimed that he is “innocent of economic knowledge” and used the words “economic” and “economics” fewer than five times in his entire Nobel Prize lecture.)

In theory and in practice, these disciplines use dissimilar methods to achieve their objectives. The table below summarizes some of the key differences (in broad strokes) of each discipline as applied to decision making:

| Psychology | Behavioral Economics | Marketing | Experimental Economics | Neoclassical Economics | |

| Tries to understand | How our behavior arises from mental processes | How we make decisions | How we buy products | How we respond to economic incentives | How rational economic agents interact with the market |

| Most influenced by | Different branches of psychology (cognitive, social, personality, evolutionary, comparative, developmental), neuroscience, and behavioral economics | Psychology and marketing science | Psychology | Economics and psychology | Philosophy |

| Research methods |

|

|

|

|

|

| Things they talk about |

|

|

|

|

|

| Things they don’t talk about |

|

|

|

|

|

So, how do these differences play out when the professors from each of our disciplines order a drink?

Psychologist

The psychologist is interested in which mental processes are going to contribute to her decision. As the experimental economist dashes into the bar after running straight from his lab, the psychologist wonders how his elevated heart rate will affect his preferences. She’s also thinking about how even her colleagues who don’t really want to drink will still have one due to social norms, and she’s wondering what it means to “feel like having a Cosmopolitan today.”

Behavioral economist

The behavioral economist is focused on the multitude of factors that lead to the decisions made in the bar each day. He recalls the psychologist’s stringent diet, and wonders if her depleted willpower from eating salads all day might lead her to drink too much. Looking at his watch, he cringes because when happy hour ends in three minutes, prospect theory tells him that people who miss it will be more upset than people who unexpectedly order during tomorrow’s happy hour.

Marketing scientist

The marketing scientist pays attention to the immediate factors that lead his colleagues to purchase particular drinks. He recognizes that the presence of expensive top-shelf liquor makes the cocktail specials feel slightly less pricey than they really are, and gnaws at whether the “50% off” happy hour special would be more successful if it were framed as “buy one, get one free.” Needless to say, since the marketing scientist does the most work with industry, he pays for drinks.

Experimental economist

The experimental economist wonders if this is a one-time interaction or if future gatherings will occur, because he knows that it will affect whether his colleagues pay back the marketing scientist as they promised. Knowing that pure altruism does not exist, he questions the motives of the bartender who tells him “the next one’s on me.”

Neoclassical economist

The neoclassical economist orders quickly, because she has a set of stable preferences. As a perfectly rational utility maximizer, she will consume whatever product (beverage or otherwise) provides the highest utility, until the marginal utility of that option falls below the next best option. At that point, she will depart from the bar to wherever her ordered preferences take her.

How Headspace Hacked Social Proof

Like most health and wellness habits, meditation has challenging behavioral characteristics:

- Requires a meaningful time commitment (10-30 minutes) and considerable consistency (daily)

- Requires a specific environment (uninterrupted, quiet, sitting, eyes closed)

- Yields long-term benefits (6+ months) with the potential for no appreciable short term gains

Many wellness apps use behavior design tactics to help overcome these barriers, but few are contextual to the nuances of the target behavior. In this regard, the popular freemium meditation app Headspace stands out in its thoughtful use of social behavior design. I’ll highlight three areas where Headspace excels and provide one recommendation for improvement.

1. A Leaderless Leaderboard

Meditation should be autotelic — done for its own sake. A gamified, badge-laden, points-driven, force-ranked leaderboard would likely be corrosive to meditation. However, if Headspace didn’t use any social features, its users would miss out on the benefits of peer accountability. Headspace strikes the right balance with a low fidelity and non-competitive “buddy” feature.

| Traditional Approach | Headspace Approach | Benefit |

| Avatars are self-selected photos | Avatars are friendly illustrations | Reduces psychological identifiability by adding distance between you and your buddies. This likely reduces the competitive drive (i.e., seeing your friend’s photo might make you want to compete with her, but it’s hard to feel competitive when you’re looking at her smiling avatar). |

| Add an unlimited number of friends through social media platforms | Add up to 5 “buddies” by email only | Incentivizes you to only add your closest companions. Meditating daily would be a lot of work to show off to just a few people, if that were your goal. |

| Friends (competitors!) are listed in rank-order, often with multiple metrics | Buddies are displayed horizontally. When you click on an avatar, you can only see a few metrics, such as the last time that person meditated. | Minimizes competitive atmosphere and prevents showmanship. You only know enough to check in and see how your buddies are doing. |

| Post comments and emoticons on a feed of activities | Nudge a buddy via text or email | Minimizes social praise or guilt as an extrinsic motivator for meditation. |

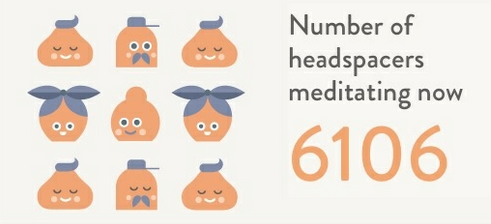

2. Subtle Social Proof

When you swipe right from the main meditation tab, you’re taken to a screen that displays your progress. Beneath your meditation statistics, the app displays the number of people meditating right now. This number is a startling reminder that at this very moment, thousands of people are actually meditating. The number is small and dynamic enough to feel credible, but substantial enough to make you feel like you’re part of a larger community with a shared experience.

If you are trying to procrastinate, that number immediately encourages you to start meditating. If you just finished meditating, it’s a subtle congratulations for joining thousands of like-minded individuals. This is a powerful way to reinforce a habit that requires persistence in light of the fact that it yields few short-term benefits.

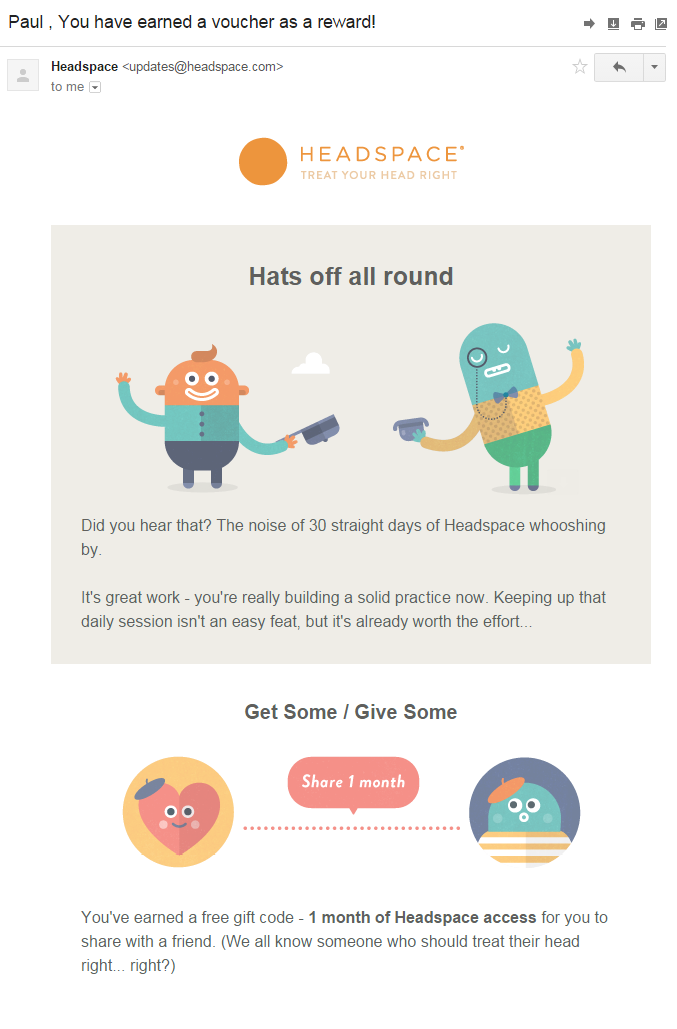

3. Non-Instrumental Social Rewards

Many apps incentivize the primary user for achieving the target behavior (e.g., mayorships in Foursquare/Swarm). However, providing users with an instrumental reward will likely undermine their intrinsic motivation. There’s a large body of literature suggesting that incentivizing an intrinsically-motivated behavior (e.g., helping a neighbor lift some heavy boxes out of a desire to be a nice person) with an extrinsic reward (e.g., $5) degrades performance. In the Headspace context, you don’t want to directly incentivize habitual meditators by giving them benefits that are instrumentally valuable. Headspace thoughtfully addresses this tension by rewarding meditators who achieve 15 or 30 day streaks with a free 15 or 30 day voucher that they can only share with a friend. Since the meditator can’t use the voucher for his own account, Headspace rewards the target behavior without corrupting the motivation, and potentially generates a referral in the process.

It is also important for users to only associate the Headspace app with the target behavior of meditation. Headspace deftly preserves the sanctity of the app by delivering the 30 day voucher code via email, which further distances the meditation experience from any incentives.

What I’d Change: Streaks

Rewarding streaks is a powerful method to encourage consistent habits. Unfortunately, streaks ignore the reality that life happens — flawless daily habits are nearly impossible. Even the most dedicated flossers, exercises, or meditators simply miss a day every once in a while.

In a behavior design context, rewarding long streaks is dangerous for two reasons:

- You incentivize cheating. If it’s nearing midnight and you just realized that you didn’t meditate, you might convince yourself that it’s okay to meditate while brushing your teeth.

- You risk demotivating users when they break long streaks. Prospect theory reminds us that losses loom larger than gains. When you break a long streak, everything you worked on so hard now feels like it’s thrown out the window because you forgot to meditate for just one day. I bet that a person who breaks a 90 day streak will be subsequently much less active than someone who only ever achieves 15 or 30 day streaks.

As a result, I’d encourage Headspace to only reward streaks of up to 30 or 60 days. You can reward 120 or 365 day streaks through surprise emails, but building it into the game dynamics distorts the core incentives.

Concluding Thoughts

Thoughtful behavior design can’t be copied. What works in one context could backfire in another. The tactics I’ve highlighted may be uniquely beneficial to Headspace given the nature of the target behavior. For example, you might want robust leaderboards when trying to encourage people to lose weight. As designers of behavior, whether for ourselves or others, we must first consider the context and then build to the design.

Happy meditating!

Designing for User Confidence: Foursquare Case Study

I’ve recently started using Foursquare as my default restaurant discovery app, but I couldn’t figure out why.

Picking a restaurant is a hard problem, but what had Foursquare done so well?

After reflecting on the user experience, I’ve noticed several key design choices that help Foursquare users feel more confident and make faster decisions. Below are three lessons from Foursquare that designers can apply to simplify and improve almost any challenging decision environment.

1. Convert qualitative data into quantitative insights

Foursquare highlights a specific area in which each restaurant excels. In this example, the restaurant in question is “One of the top 10 places for chicken fingers in New York.” Wouldn’t it feel good to invite your friends to the #5 burger joint in Midtown East, the #1 coffee shop in SoHo, or the #3 Italian restaurant on the Upper East Side? That’s an insight that actually helps you achieve your goal.

Yelp |

Foursquare |

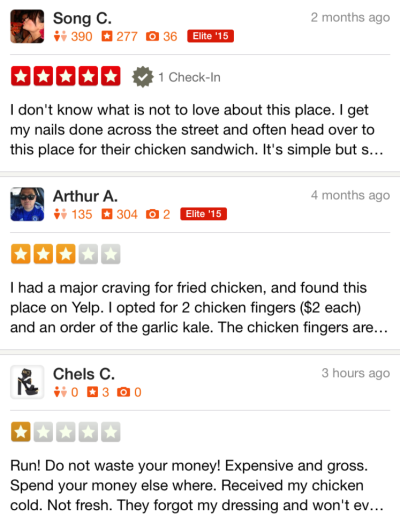

2. Avoid conflicting information

Conflicting information requires a degree of cognitive effort that can paralyze choice. We’re all familiar with the pattern: You read a string of positive restaurant reviews followed by a dramatic story of food poisoning at a birthday dinner. Back to the search results. You pick a new restaurant, read more reviews, and start paying attention to the credibility of each review. You uncover that the beef is popular, but at least three Yelp Elite experts point out that the appetizers are spotty and that they always overcook the vegetables. There’s so much negative information that you start making complicated comparisons on the downsides of each restaurant: Should you go to the 4 star Italian place with 107 reviews but overcooked vegetables and spotty appetizers, or the cheaper 4.5 star Indian place with only 14 reviews but which someone said has the best chana in all of Queens? Soon enough, no restaurant looks like a good option. Whoops.

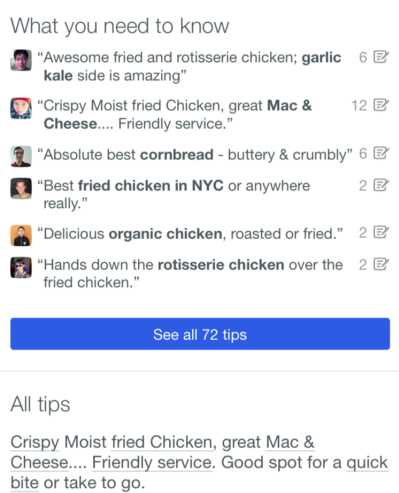

Foursquare avoids the demotivating stories of diarrhea birthdays and spilled drinks on the third date. Instead of serving up reviews, Foursquare provides positive tips that make you feel like you’re getting the inside scoop. These helpful tips build confidence in a restaurant and require little cognitive effort.

Yelp |

Foursquare |

3. Make it easy to solicit meaningful information

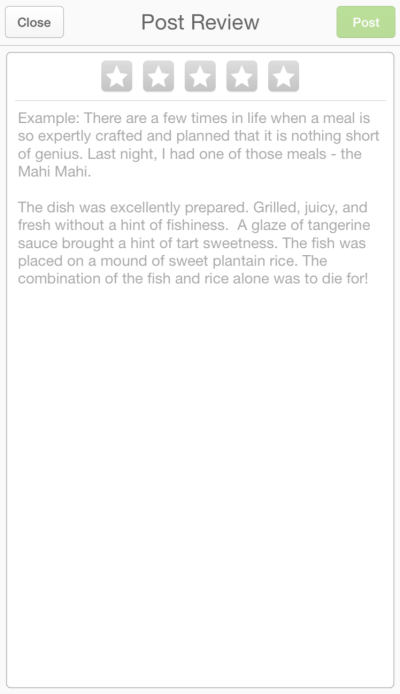

Yelp solicits long-form narrative reviews. Even the text box is ghosted with a sample review to prompt detailed stories. However, average users are unlikely to write such extensive narratives, and it’s hard to systematically extract insights from volumes of free text.

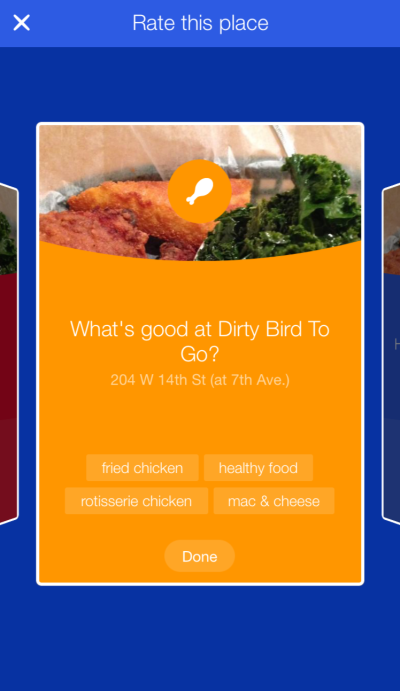

Instead of requesting a review, Foursquare asks a few simple questions that don’t require much effort, such as:

- Did you like the restaurant? (yes, it’s okay, or no)

- What’s good here? (select text from a list)

- Is the restaurant romantic? (very, somewhat, not at all)

- Is it good for families? (very, somewhat, not at all)

- Is it good for late nights? (very, somewhat, not at all)

The questions are easy, you can respond with one tap, and you can stop at any time. By making the restaurant ranking process easy, fast, and fun, Foursquare can collect meaningful structured data from its users. This structured data allows Foursquare to generate confidence-instilling context, such as the “top 10 chicken finger” ranking for each restaurant.

Yelp |

Foursquare |

Concluding Thoughts

Choices with many subjective attributes, such as picking restaurants or buying clothing, present unique challenges to the design of decision support tools. To reduce the decision space, most search and discovery or e-commerce tools only provide basic filtering functions. While it’s helpful to hide restaurants that aren’t open or perhaps prioritize restaurants within walking distance, there are usually so many options left over that it’s still hard to make a decision. By intelligently capturing, processing, and displaying relevant insights, Foursquare’s mobile app simplifies options and instills choice confidence. Designers of other subjective choice environments can look to Foursquare as a case study on behaviorally-intelligent design.

A Behavioral Lens on Being Mortal

What would you be willing to trade to live for two more months? Would you risk paralysis of your lower body? Would you go on a feeding tube? Or would you rather accept death?

These are the difficult choices that face many patients and their caregivers. In Being Mortal, Dr. Atul Gawande argues that end of life care tends to focus on increasing the patient’s length of life, while sacrificing quality of life. In light of this dilemma, Dr. Gawande urges us to be more thoughtful when considering end of life treatment options. We should make deliberate choices that adhere to our personal definition of well-being. While one individual might accept a high risk of paralysis in exchange for the ability to watch football and eat ice cream, others might make radically different tradeoffs.

Looking at Being Mortal through a behavioral lens reveals a parallel argument: in order to support individual well-being, end of life care must focus on goals rather than preferences. To understand why, we can look to one of the most challenging human biases – the empathy gap.

Empathy gaps occur when we overemphasize our current “hot” emotional state and miscalculate our future “cold” state behavior (Loewenstein, 2005). The binge drinker who swears off alcohol at the height of inebriation offers a perfect example of the empathy gap in action. Overwhelmed by visceral pain and preoccupied with his emotional state, he vows to never drink again. What he doesn’t realize, however, is that his choice is heavily influenced by his “hot” state. After sobering up and returning to a “cold” state, he forgets the ill effects of inebriation and repeats the cycle at the next party.

The binge drinker in this example teaches us that a choice made in one state might not hold up in the other, because visceral factors like hunger, thirst, pleasure, and pain can cloud our judgment.

Now consider three common preferences in a living will:

- Do you want cardiopulmonary resuscitation if you heart ceases to function?

- Do you want mechanical respiration if you are unable to breathe unassisted?

- Do you want artificial hydration or nutrition if you are unable to eat or drink?

How can we expect a healthy individual sitting in a lawyer’s office to accurately make choices about a distant hypothetical life-threatening situation? Even in the cold state of good health, about 1 in 3 individuals will reverse their preferences for life-sustaining interventions at least once in a two-year period (Danis et al., 1994; Ditto et al., 2003). This cold state indecisiveness makes it difficult to generate authentic living wills in times of health. Add to that the hot state complexity of living with dementia or paralysis, and making end of life choices looks like a losing behavioral proposition. This cold-to-hot state empathy gap represents the inverse problem of the binge drinker, yet it is just as difficult to overcome.

Now consider some of the questions mentioned in Being Mortal:

- What is your understanding of your situation and its potential outcomes?

- What are your fears and what are your hopes?

- What are the trade-offs you are willing to make and not willing to make?

While Dr. Gawande acknowledges the importance of assessing preferences for life-sustaining interventions, he appears to focus primarily on a patient’s goals for living. The behavioral literature supports this approach in theory, as goals are more durable than preferences. When we set goals, we draw on our experiences in order to decide what we want to achieve. While goals shift as an individual moves through life, preferences are significantly more susceptible to empathy gaps and other context biases, such as framing. Some of these biases are fairly minor, but others will cause us to make critical mistakes. This is especially true when we are asked to make choices about situations with which we have little to no experience, which is often the case for end of life care.

As I’ve written before, the behavioral literature can only offer heuristics and guardrails for optimizing choice and mitigating bias. Ultimately, medical professionals must negotiate these behavioral hurdles and help their patients to make the right tradeoffs.