The Problem of Egocentrism in Societal Advancement (and Some Potential Solutions)

We should anticipate significant changes in our economy and society in the next 10-15 years concomitant with the increasing rate of technological innovation. However, many people underestimate just how different our future could be. If we want to do a good job preparing for societal transformation, which will likely require hard collective choices about the framework of how we live and work with each other, we’ll have to figure out how to get people to understand what the future might hold.

Several biases lead people to struggle to imagine a future radically different from the present. This is a significant threat to preparing for future societal change. However, one of the most interesting and potentially solvable biases is the forecasting error induced by egocentrism. When we consider the future, we imagine our own experiences today with some incremental augmentation (e.g., “I’ll be a senior software engineer with, like, a really fast laptop that charges wirelessly. And we’ll definitely have better cancer drugs.”). By projecting our current egocentric reference points into the future, we end up telling ourselves a story that looks much like the present, despite the fact that the future rarely looks like the present (e.g., social platforms don’t look anything like search, immunotherapy doesn’t look like chemotherapy).

What’s interesting about this reference point problem is that we might be able to correct for it by reminding people of the concurrent societal differences that exist today.

For example:

- In Norway, each individual’s income and taxes are published online for anyone to see.

- Over 90% of households have peanut butter in the USA, and two of our presidents used to be peanut farmers. While peanut butter is ubiquitous in American culture, it is rarely consumed in most other countries. Similarly, Americans consume over 30 pounds of cheese per year, but it’s almost impossible to find in China.

- Japan has one of the highest adoption rates in the world, but over 90% of adoptees are adult males in their 20s and 30s. One cause is that old Japanese civil codes required that wealth be passed through male inheritance, and while the laws have changed, the habit remains. As a result, it is not uncommon for executives to adopt their adult successor to maintain family lines.

- Divorce to marriage ratios vary by over 650% (9% in Jamaica, 71% in Belgium).

- The average life expectancy at birth varies by over 70% (49 in Swaziland, 84 in Japan).

It’s an exercise in empathy: consider how different your life might be if you expected to live to 50 instead of 75. In less than 24 hours, you can fly to a country where the basic building blocks of your life — your goals, values, ambitions, how you spend your time, if/when you have children — would all be radically different. Reminding ourselves of the current heterogeneity of the most basic life experiences might help us recognize the magnitude of change that could occur in the future.

Three Ways to Fix Personal Finance with Behavioral Economics

We’re awful at personal finance.

It’s not because we’re dumb — it’s just that personal finance is a minefield of cognitive biases.

Consider almost any cognitive bias: procrastination, planning fallacy, confirmation bias, affective forecasting errors, endowment effects, sunk costs, or hyperbolic discounting. Each of these biases leads to poor decisions that impede our financial goals.

Despite the proliferation of cognitive biases in such an important domain, most personal finance apps don’t even attempt to help us make better decisions. Today’s utilitarian banking tools merely replicate first-order IVR-style transactions of the 1970s (e.g., view account balance, transfer money, pay a bill).

A next generation personal finance app — let’s call it a Behaviorally Intelligent Advisor (BIA) — could leverage insights from behavioral science to nudge us to make decisions that serve our goals. To this end, I’ve sketched some early thinking on how one might design a BIA with behavioral science in mind.

1) Reframe Transactions (and Kill the Ledger)

Unless you have cash flow concerns, the time-based ledger is generally an irrelevant lens on personal finance. A BIA should automatically lump and split transactions to help us think about our money in ways that maximize hedonic value. Prospect theory and mental accounting, which I wrote about in a previous article, inform how a BIA might display financial transactions:

- Separate gains. We can maximize the hedonic impact of gains by spreading them across separate temporal instances. For example, receiving two bundles of $1,000 is better than one bundle of $2,000.

- Combine losses. A BIA should minimize the pain of losses by aggregating expenses into a single episode. For example, we’d rather pay $10 in bank fees all at once than pay $1 in bank fees ten separate times.

- Combine small losses with large gains. The interaction of loss aversion (i.e., losses loom larger than gains) with diminishing sensitivity for gains (i.e., $10 is significantly better than $5, but $105 isn’t that much better than $100) suggests that we can maximize hedonic utility by combining smaller losses with larger gains. For example, a BIA might automatically lump your paycheck income of $2,250 and transit expenses of -$100 into a single episode of $2,150. While the resulting income of $2,150 is slightly worse than $2,250, you avoid the pain of an independent -$100 transit expense loss episode. In a similar vein, a BIA might amortize costs over the span of consumption to maximize hedonic value. For example, depending on the flow of income and expenses, it might make sense to represent a mortgage payment as a series of small daily payments instead of a monthly lump sum. This reorganization might minimize the perception of losses, especially if the small mortgage payments are netted against a larger daily gain (i.e., a paycheck similarly amortized over the pay period).

- Separate small gains from large losses. The value function for gains is concave and steepest near the origin, so a BIA could maximize hedonic value by segregating small gains from large losses. Consider the intuition: if you win $150 at a casino, you don’t want to mentally integrate that win with your $5,000 credit card debt. We feel better about a small gain of $150 and a seemingly unrelated loss of -$5,000 from a different mental account than a single integrated loss of -$4,850. A BIA could integrate and split transactions to maximize the emotional perception of our finances.

2) Set and Frame Goals

Labeling our money allows us to control how we allocate our resources, which is particularly important to achieve our goals. Many of us have set of goals (e.g., take a vacation in late September, buy a new refrigerator, and save for a deposit on a car in 6-9 months), but our savings accounts merely represent broad pools of money (e.g., $12,521 in savings) that are untethered to those goals.

A BIA should help us create goal-based, partitioned financial accounts that reflect important goals. For example, you might have several goal-oriented pools of money, such as a vacation savings fund (e.g., goal to save $5,000 by September 15th), a refrigerator savings fund (e.g., goal to save $1,000 by end of year), and a new car fund (e.g., goal to save $4,000 by February 1st of next year). You might also want an emergency savings fund and a “fun money” fund. The BIA should solicit your goals and help you decide what you need.

Several behavioral tactics might enhance a goal-based account architecture:

- Goal acceleration. We exert more effort as we approach goal completion (i.e., the goal gradient effect). Creating an illusion of progress can spur us to achieve our goals more quickly. You’ve likely seen the instantiation of this effect with loyalty cards. Instead of giving patrons a 10-hole punch loyalty card, many restaurants offer a 12-hole punch card initialized with two punches. When we start with two punches toward our 12-hole goal, we return to the restaurant more frequently than we do with the 10-hole punch loyalty card. Instead of framing a financial target based on existing progress (e.g., a goal of saving $4,000 for vacation because you’ve already saved $1,000), a BIA might pre-initialize certain goals with existing funds to create the perception that you’ve already made progress (e.g., you’re already $1,000 into your $5,000 vacation goal).

- Goal chunking. In a similar vein, a BIA could compute the plausibility of achieving each goal given historical financial patterns and intelligently chunk goals into smaller and more achievable subgoals. For example, a BIA might break a $2,500 savings goal into segments of $750, $1,250, and $500. This tactic yields a second benefit: non-linearity likely yields more engagement than the traditional linear (i.e., boring) savings behavior.

- Goal salience. Increasing the identifiability or salience of goals can help fight procrastination. For example, seeing a photo of your daughter will likely encourage you to allocate more savings for her college tuition.

- Social pressure. Many people respond to social cues, and a BIA could leverage the multitude of social motivational mechanisms to encourage goal-directed behavior. Competitions among family, friends, or other small social group may encourage progress. A BIA might also leverage social norms to enhance motivation. For example, if a BIA conveyed that 82% of people in your income range have an emergency fund of at least $5,000, you might be more likely to adopt and make progress toward that objective.

- Consistency. We generally prefer to act consistently with our prior behavior. A BIA might surface our previous actions to nudge us toward normatively desirable behavior (e.g., “Last year you allocated 75% of your tax refund to your retirement plan. Would you like to do that again?”).

3) Enable Better Decision Making

It often takes hundreds of individual decisions to make progress against a meaty financial goal. A BIA should systematically counteract the cognitive biases that would otherwise lead us astray. Behavioral science offers a broad toolkit that a BIA could use to improve decision making:

- Precommitment. Since income is typically cyclical, a BIA might analyze progress toward each goal and ask us to precommit to a specific allocation for our next paycheck (e.g., “You’re slightly behind your retirement goal. Do you want to allocate $500 from your next paycheck to your retirement account?”).

- Active choice. In addition to nudging us toward action, prompting active tradeoffs can also mitigate reactance by reminding us of our own autonomy. For example, instead of asking whether you want to allocate $500 into a retirement fund, a BIA might suggest two options: a) allocate $500 into a retirement fund, or b) $400 into a retirement fund and $100 into a “rainy day” fund. This encourages you to make a decision by presenting you with multiple options, and also reminds you that you are in control.

- Concreteness. A BIA should help us understand the concrete tradeoffs of each option, especially among options defined by factors that are difficult to compute, such as compounding interest. A BIA could leverage multiple techniques, such as concreteness and loss aversion (e.g., “I see that you don’t want to make any payments on your credit card this month. If you pay your credit card in full next month, you will pay an extra $40 in interest. If you keep delaying your credit card payments for another year, you will pay an extra $500 in interest.”). Likewise, a BIA could point out that a $500 deposit into a retirement account today could grow to $2,000-$3,000 in 25 years. A BIA might also help counteract the overoptimism bias by accurately representing progress against goals in concrete terms. For example, a BIA might compute a retirement readiness age equivalent (e.g., your target retirement age is 55, but given your finances, your “real” retirement age is 62).

- Smart defaults. A BIA should employ a default configuration that reflects normative financial preferences, such as automatically paying off high interest accounts before allocating income to savings.

- Strategic anchoring. A BIA could use certain behavioral biases, such as anchoring, to counteract others, such as procrastination. For example, a BIA might ask you “How much do you want to save for retirement?” before prompting you to decide how much of your paycheck you want to allocate to that goal.

- Prepayment. Decoupling the pleasure of consumption from the pain of paying increases the hedonic value of experiences. As a result, when we pay up front, we can control consumption and enjoy our experiences more. For example, a BIA could help you budget and prepay (ideally months in advance) for the helicopter ride you’ve been dreaming of so that you’re not thinking about costs while you’re enjoying the experience.

- Cooling off periods. Unexpected income, such as a large bonus, can erode self-control and cause risk-seeking behavior (i.e., the house money effect). A BIA could help us avoid impulsive behavior by instituting cooling off periods that limit use of unexpected funds for a fixed period of time.

Thoughtfully crafting a BIA in the personal finance arena is challenging for a variety of reasons, including regulation that may make it difficult to implement some of these concepts. Nevertheless, it’s a useful thought exercise that may spark additional thinking on how we can help consumers make better choices in an important domain.

Why Iron Free Dominates Wrinkle Free: Lessons for Marketers

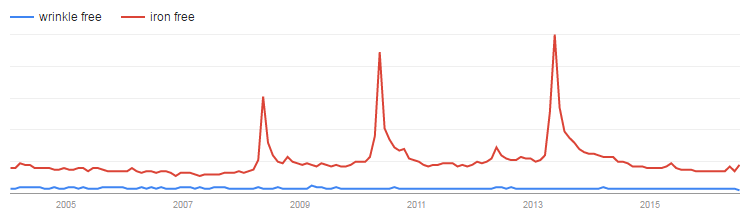

There are multiple ways to position a product. Marketers often highlight product features, such as “wrinkle free.” However, we know that it’s often best to address specific consumer pain points, such as “iron free.”

It is clear from Google Trends that the pain point solution “iron free” dominates searches, and its cyclicality likely reflects actual consumer need. This makes sense; consumers have needs and seek solutions for our needs more than we seek specific features, which are merely instrumental.

We would assume that the market positions products in response to consumer needs. However, a brief Amazon search found over 1 million results for “wrinkle free” (i.e., the product feature), but fewer than 5,000 results for “iron free” (i.e., the consumer pain point).

While consumers search for “iron free” 8-30 times more often than “wrinkle free,” products matching “wrinkle free” are 250 times more common on Amazon. Features are nice, but pain point solvers are powerful. This is a simple example — one of many, I imagine – where the market isn’t using language that reflects consumer demand.

Harvesting Sunk Costs for Happiness

Sunk costs are irrecoverable investments of time or money. Since sunk costs were already spent (i.e., we can’t re-spend the $100 that we already spent on non-refundable soccer tickets), it’s irrational to include them in our decision making. The fact that we spent $100 on soccer tickets should not influence whether we subsequently attend the game; we spent $100 regardless of our future choice. However, we frequently make decisions based on sunk costs; we decide to attend the cold and rainy soccer game even though we’d prefer to watch it from the comfort of our home, simply because we feel attached to the $100 we already spent. This error is called the sunk cost fallacy.

While sunk costs often lead to bad decisions (e.g., over-investing in a dead end project, a failing relationship, or a boring book), we can harness this bias for good. A few obvious examples come to mind:

Gym: Even though the gym membership is a sunk cost, some people visit the gym more frequently in order to lower the effective unit cost. While using the gym more often “because I paid for it” is irrational, this sunk cost-based thinking likely leads to a positive outcome.

Attire: After investing in an expensive clothing article, such as a tuxedo, tailored suit, or a designer purse, we often look for occasions where we can make the most of our purchase. Perhaps we attend more parties, meet new people, feel more confident, or receive more compliments as a result. There’s little harm in falling prey to the sunk cost fallacy in this way.

Vacation Properties: Once we spend money on a timeshare or a vacation home, we may feel a need to vacation more in an attempt to make the most of our investment. Given that most vacation days go unused, the sunk cost fallacy might nudge us in a normatively positive direction.

Our biases around sunk costs suggest a general strategy in which we should make investments in domains that lead us to behaviors that we normatively prefer. By tapping into our deep tendency to feel drawn to sunk costs, we can potentially harness our biases to help achieve our goals.

Why Do We Eat Booger Jelly Beans? Lessons from Utility Theory.

In general, we try to make decisions that we think will maximize our expected utility. Typically, we conceptualize expected utility as a property resulting from the product we buy — i.e., we buy chocolate cake because it tastes good.

So why do people buy booger flavored Jelly Beans?

To answer this question, we have to revisit how we think about utility. In addition to the utility of a product, we might also derive utility from the process of buying a product. In other words, we buy booger flavored Jelly Beans not because they taste good, but because they are fun to buy.

In fact, there’s a class of products that offer little utility themselves, but from which we derive some utility through the process of buying. It’s also likely that the fleeting utility we experience in the process of buying these products leads us to mispredict the utility we’ll subsequently experience when we consume or use the product. I’d bet that after a few bites of booger Jelly Beans, the rest will end up in the pantry for months before they’re finally discarded.

The gap between these two forms of utility means that at least some of the products we enjoy buying the most are also the ones we’re most likely to regret. Buyer beware!